Ghosts of the past: Why Pakistan is in perpetual crisis

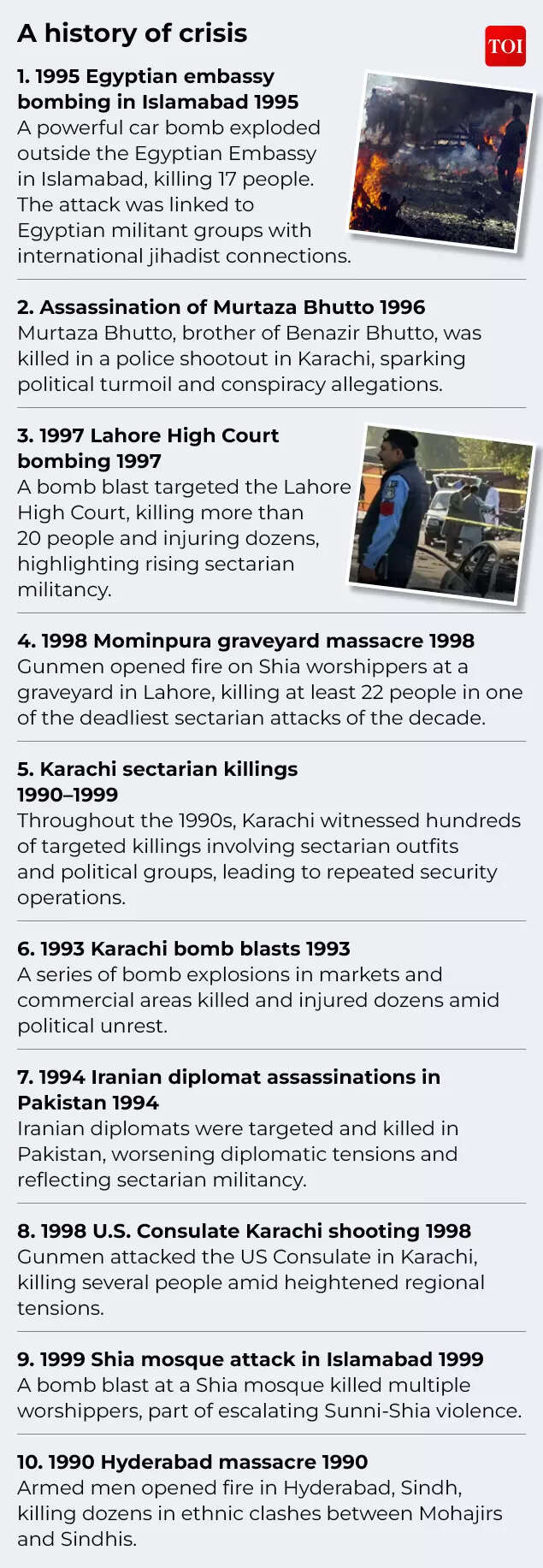

Pakistan’s crises rarely come as surprises anymore. A bombing, political upheaval, economic scare or diplomatic rupture, each seems sudden, yet for many Pakistanis, the sequence felt uncomfortably routine.In recent weeks, Pakistan has once again found itself gripped by familiar scenes. A bruising defeat to India on the cricket field. Days earlier, a suicide blast rocked the country’s capital leaving over 30 dead.

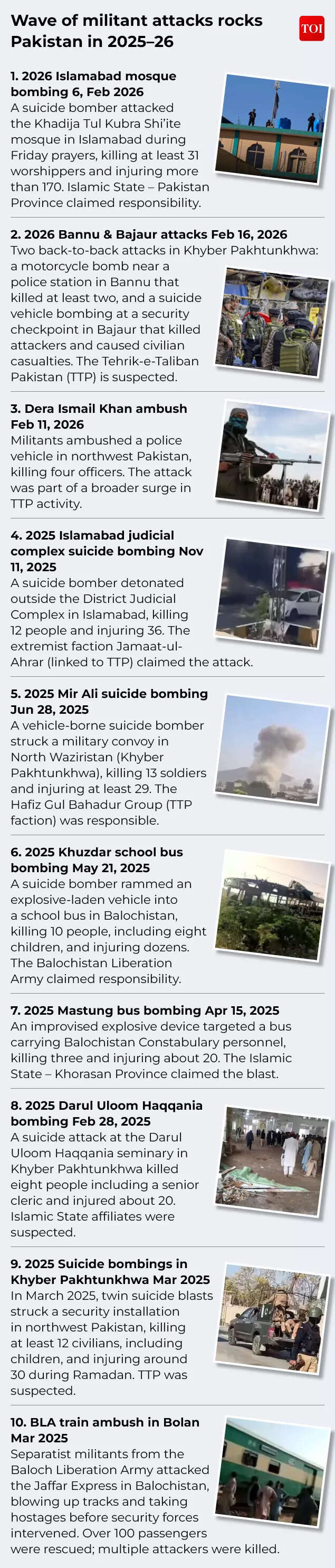

This sense of repetition is not confined to sport or security. It reflects a deeper pattern that has shaped the country since its birth in the violence of Partition in 1947. The trauma of that moment, compounded by the early death of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, left fragile institutions and an identity defined largely in opposition to India. Over decades, insecurity hardened into structure.Military coups in 1958, 1977 and 1999 entrenched the army as the ultimate arbiter of power. Islamisation under General Zia-ul-Haq reshaped law and society. The Afghan jihad cultivated militant networks that later turned inward. Economic crises became cyclical, with repeated IMF rescues substituting for structural reform.Today, as Islamabad once again balances between Beijing and a tentative re-engagement with Washington amid economic strain and regional tension, the echoes of earlier decades are unmistakable.Pakistan’s predicament is not defined by a single crisis. It is defined by the normalisation of the crisis itself.

Founding trauma and identity insecurity

Pakistan’s birth was traumatic. Violence and mass migrations at Partition shattered families and communities; in 1947–48 the first Kashmir war was fought before state institutions were firmly in place. Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s premature death in 1948 deprived the country of its strongest unifying leader.As per a report in SouthAsianVoices, Pakistan’s sense of self was cast more in counterposition to India than in an affirmative vision. “Excessive focus” on “who we are not” has defined politics from the start. In practice this meant viewing Pakistan’s survival through an India-centric lens.The “ghost” of 1947 is this embedded insecurity. Rather than a mature nation-state, Pakistan began as a creation beset by doubt, and that inherited doubt has lasted. Identity politics is still often reactive, seen in generations that speak of “India’s aggression” or cling to symbols of Muslim nationalism. This persistent identity insecurity helps explain why national crises are seldom questioned for domestic causes – instability is instead blamed on foreign conspiracies or imposed threats.At the same time, Cold War geopolitics profoundly shaped Pakistan’s trajectory. As a frontline ally of the United States in the 1950s and again during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s, Pakistan’s military establishment gained external funding, weapons and international legitimacy.

This empowered generals vis-à-vis civilian politicians in ways Partition alone cannot explain. Domestic elite bargains also mattered: landed families in Punjab and Sindh aligned with the bureaucracy and officer corps to preserve patronage networks rather than pursue land reform or broad-based taxation. Even civilian leaders such as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif weakened institutions when politically expedient.Yet Partition alone cannot explain Pakistan’s trajectory. India too was devastated by the same partition, fought multiple wars, but its military never emerged as a political arbiter, and it is on track to become the third largest economy.Bangladesh, after its own traumatic birth in 1971 and periods of military rule, gradually consolidated a civilian-dominated system. The divergence suggests that Pakistan’s crisis is not simply the inheritance of 1947, but the result of specific institutional bargains and strategic choices that entrenched security over civilian supremacy.

Military dominance and the security state

Pakistan’s early history gave the army a level of power that has shaped the country ever since. In 1958, General Ayub Khan overthrew a weak civilian government in a coup and took control. Nearly two decades later, in 1977, General Zia-ul-Haq imposed martial law and later ordered the execution of former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1979. In 1999, General Pervez Musharraf removed Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif from office. Even in more recent years, the military’s influence has played a decisive role in determining who governs.Altogether, Pakistan has spent almost half of its existence under direct or indirect military rule. As a result, the army is often described as the country’s real judge and jury, with civilian leaders allowed to remain in office only if they stay within the boundaries set by the generals.

Over time, the military has become far more than a security institution. It is widely seen as the most powerful body in the country. Recent prime ministers have had to work in close alignment with the army leadership. When relations between Imran Khan and the generals deteriorated in 2021, he was removed through a parliamentary vote of no confidence. Khan described the episode as a foreign-backed conspiracy, a claim rejected by the United States. Since then, observers say the military has tightened its grip. The opposition in Pakistan argues that state institutions have been used to sideline Khan, whose popularity was viewed as a challenge to the existing order. Civilian governments often depend on military support to survive, and key issues such as relations with India and Afghanistan are largely managed through military channels, even when elected leaders are formally in charge. The army’s influence is also reflected in the national budget. Pakistan consistently spends around 1.9 to 2.0 per cent of its GDP on defence, a significant share for a country facing serious economic pressures. In June 2025, the government announced a 20 per cent increase in defence spending, raising it to 2.55 trillion rupees, about 9 billion dollars. This was the largest rise in a decade. The increase came at a time when the overall budget was cut by nearly 7 per cent under pressure from the International Monetary Fund. While officials cited tensions with India in May 2025 as justification, critics warned that higher defence spending could reduce funding for education, healthcare and social welfare. In the 2025 to 2026 fiscal year, total government spending fell to 17.57 trillion rupees, yet defence continued to expand. Over five years, the military budget has nearly doubled, even as other sectors have faced strict financial limits.

Islamisation and ideological statecraft

General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime marked a decisive ideological shift. To legitimise his rule, Zia pursued a programme of Islamisation that transformed Pakistan’s legal and social fabric. The Hudood Ordinances, expanded blasphemy laws and the creation of the Federal Shariat Court embedded religious authority within state institutions.Islamisation altered education, finance and judicial structures. Yet its long-term consequences were destabilising. Sectarian divisions intensified, minorities became more vulnerable and hardline groups gained legitimacy. Blasphemy allegations have since triggered repeated mob violence, while sectarian outfits expanded their reach.Successive governments have hesitated to reform these laws, fearing backlash from religious movements. As a result, ideological rigidity persists. The appeal to protect Pakistan’s “Islamic character” remains a potent political tool, narrowing space for pluralism and reform.Islamisation’s “ghost” still haunts Pakistan’s politics. Successive governments, even civilian ones, have largely left Zia’s laws in place. The narrative that Pakistan must defend its “Islamic character” persists. Religious parties and movements frequently use the Pakistanis’ strong faith identity as a political cudgel or rallying cry. For example, in recent years even nominally centrist parties dare not question blasphemy statutes, lest they be attacked by hardliner factions or face street protests.

Afghan Jihad and militant blowback

A key chapter in Pakistan’s contemporary crisis began during the Afghan war of 1979 to 1989. Islamabad became a frontline state in the United States backed campaign against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Pakistan’s military and the Inter-Services Intelligence agency trained, armed and sheltered Afghan mujahideen fighters and, in later years, facilitated the rise of the Taliban. At the time, this alignment served Washington’s interests and kept Soviet forces under sustained pressure. Yet internal military discussions later revealed a more complex calculation.That approach delivered limited short term advantages but imposed heavy long term costs. Pakistan did gain leverage in Afghanistan and, until 2021, benefited from a broadly sympathetic administration in Kabul. However, the consequences at home were severe. The networks and fighters cultivated during the anti Soviet jihad did not dissolve once the conflict ended. Many regrouped and redirected their violence inward. The Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, formed in 2007, drew from these militant strands. Attacks that had once been sporadic became frequent and deadly. Areas in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, including the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas, turned into insurgent strongholds, while major cities experienced suicide bombings and sectarian violence.The war in Afghanistan also destabilized Pakistan’s western frontier. Militant sanctuaries in Afghanistan allowed insurgents to regroup across the border. Islamabad for years accused Kabul of harbouring anti-Pakistan fighters and vice versa; this tit-for-tat fueled distrust. Most dramatically, after the US withdrawal in 2021 and the Taliban’s return to power, the TTP resurged from Afghan soil. Pakistan’s army chief warned that “attacks in Pakistan have surged” – up 28% in 2022 and a staggering 79% in the first half of 2023 – with the TTP openly striking law enforcement. In one sense, it was a mirror of decades past: just as Pakistan had once hosted the Afghan Taliban, it was now confronted by Pakistan’s Taliban on Afghan ground.

Economic fragility and IMF dependency

Parallel to its political instability, Pakistan has faced almost constant economic difficulty. High defence spending, combined with long standing fiscal mismanagement, has left the country exposed to repeated crises. For decades, Islamabad has relied on support from the International Monetary Fund. Pakistan is one of the IMF’s most frequent borrowers, entering at least 25 programmes since 1958, more than any other country. Nearly every government, whether military or civilian, has turned to the Fund at some point. The threat of default has often come close, only to be avoided at the last moment.Deep structural weaknesses lie at the heart of this fragility. One major problem is the narrow tax base. Tax revenue has remained stuck at around 10 to 12 per cent of GDP, which is low by global standards. Even during periods of economic growth, governments have struggled to collect sufficient taxes from wealthy individuals and large industries. At the same time, energy subsidies and mounting circular debt continue to strain public finances. In the power sector, unpaid bills between companies build up when tariffs are kept artificially low. Each IMF programme has required reforms to address this, usually involving higher electricity and gas prices. These measures are politically unpopular and often only partly carried out. Corruption and the influence of powerful elites have made matters worse. A recent IMF assessment stated that widespread corruption, including special tax exemptions and manipulated procurement processes, is undermining the economy. An analysis by Al Jazeera suggested that corruption costs Pakistan roughly 6 per cent of GDP each year. Politically connected businesses often receive easier access to loans, default more frequently, and influence policy decisions in their favour. This weakens competition and reduces public confidence in reform efforts. Experts warn that no political leadership has shown the resolve to challenge these entrenched interests, leaving economic planning vulnerable to reversal. The result is a cycle of recurring crisis. Governments rely on short term fixes under IMF supervision, cutting expenditure in some areas while raising tariffs in others. In mid 2025, Finance Minister Aurangzeb reduced the overall budget by 7 per cent while allowing defence spending to rise by 20 per cent. Although he described the economy as stabilised, many citizens continue to struggle. Inflation, though lower than its peak near 40 per cent, still erodes incomes.

Peripheral fault lines

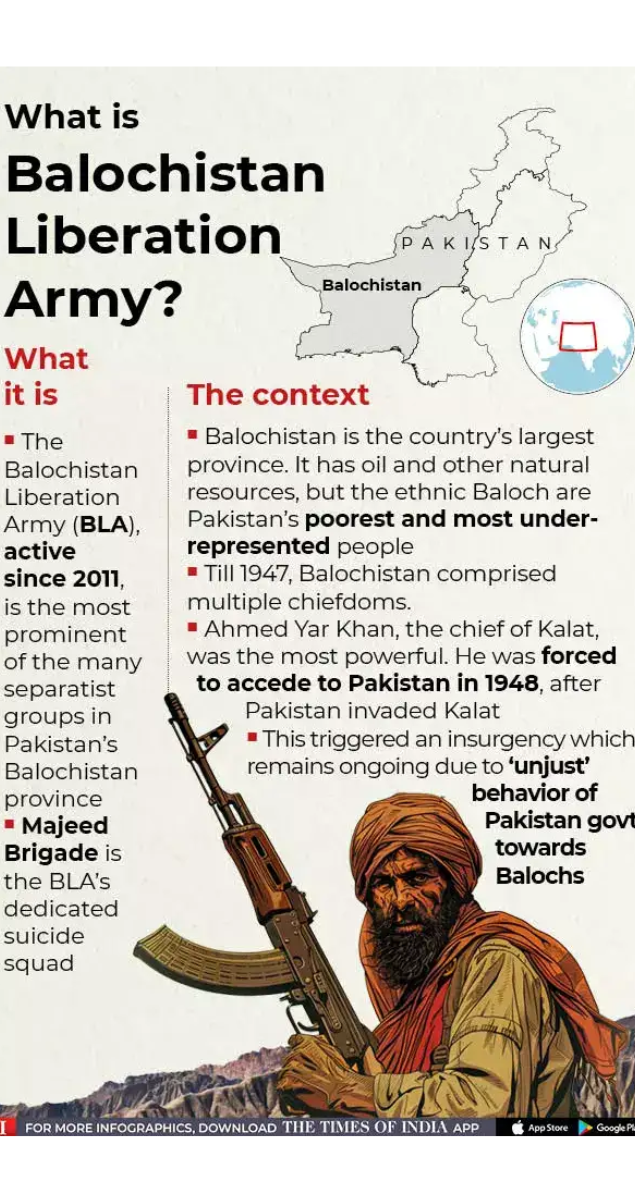

Beyond the centre, Pakistan is divided along regional and ethnic lines, often violently so. Balochistan, the vast southwestern province, is a flashpoint of secessionist rebellion. Despite its size and resource wealth, Balochistan has long complained of economic neglect and political exclusion. Independents and militants demand either greater autonomy or outright independence — and Pakistan’s response has traditionally been hard military action.In February this year, coordinated attacks by Baloch insurgents, including the Baloch Liberation Army, killed dozens of civilians and security personnel.The regional government’s reaction was blunt: Balochistan’s chief minister said only a military solution, not dialogue, could handle the problem.In late 2025, the authorities even declared dozens of peaceful Baloch activists “proscribed” under anti-terror laws, severely restricting their movements. Such measures may momentarily suppress violence, but they leave unaddressed the core grievances: a lack of education, jobs and political voice for Baloch youth. Without tackling these, the “cycle of revolt” in Balochistan – rebellion, military action, temporary calm – is likely to repeat.

In the west and north west, Pashtun majority areas face similar tensions. These regions, once central to the Afghan jihad, are home to many displaced and disenfranchised communities. The Pashtun Tahafuz Movement emerged to demand justice for enforced disappearances and civilian casualties linked to security operations. The government views the movement as a threat to state authority. In October 2024, it was formally banned. By late 2025, courts had issued non bailable warrants for its leader and other figures in sedition cases.Violence has also targeted Chinese nationals linked to projects under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor. In recent years, insurgent groups have attacked Chinese engineers and workers in Balochistan, viewing them as symbols of federal control and foreign exploitation. Deadly assaults on Chinese convoys and construction sites have heightened tensions and prompted an even stronger security presence around CPEC infrastructure.

A cycle that goes on, and on

Pakistan’s crises do not erupt from nowhere. They follow a script written decades ago. Identity shaped by fear, power concentrated in uniform, ideology woven into law, militancy cultivated for strategy, and an economy patched up rather than rebuilt. Each shock, whether political turmoil, insurgent violence or fiscal emergency, appears sudden. In reality, it is the latest turn of a well worn wheel.The question is no longer why Pakistan faces recurring instability, but whether its leaders are willing to confront the assumptions that sustain it. Can security be redefined beyond rivalry with India. Can civilian authority truly prevail. Can economic reform challenge entrenched privilege rather than protect it.Nations are not prisoners of their origins. But they are shaped by the stories they choose to repeat. Until Pakistan rewrites its foundational narrative, crisis will remain not an interruption of its history, but its steady pulse.